Language models are injective and hence invertible

This is the title of a recent preprint

(Nikolaou et al. 2025)Quick link: ArXiv:2510.15511.

, that has some

interesting insights on the mathematical properties of Transformers

when viewed as functions.

The immediate reaction is “this is nonsense”, and the title may be

viewed as either misleading or deliberately provocative in order to

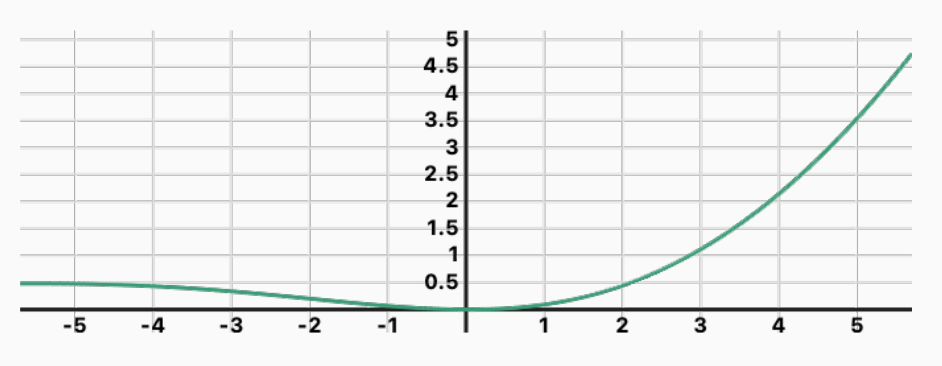

gather interest. Indeed, most functions inside neural

networks The

SwiGLU activation function. It is clearly not injective.

The

SwiGLU activation function. It is clearly not injective.

and particularly Transformers are not

injective. One thinks immediately of activation functions,

normalization layers, and so on, counter-examples abound. So how can

an entire language model be injective?

At a higher level, injectivity seems like an even taller order. From

the user’s point of view, plenty of input prompts will lead to the

same answers (one can think of all prompts ending with “answer with

yes or no”)Indeed, the public discourse around this paper was

dismal, with thousands of users on X/Twitter posting ChatGPT

screenshots “disproving” injectivity…

.

So, let’s actually go through the paper to understand the claim more precisely!

Language models as functions

There are many different ways of viewing language models as mathematical functions. In the first intuition above, we considered models as functions from vectors to vectors, or from text to text. This is what makes the result seem counter-intuitive at first.

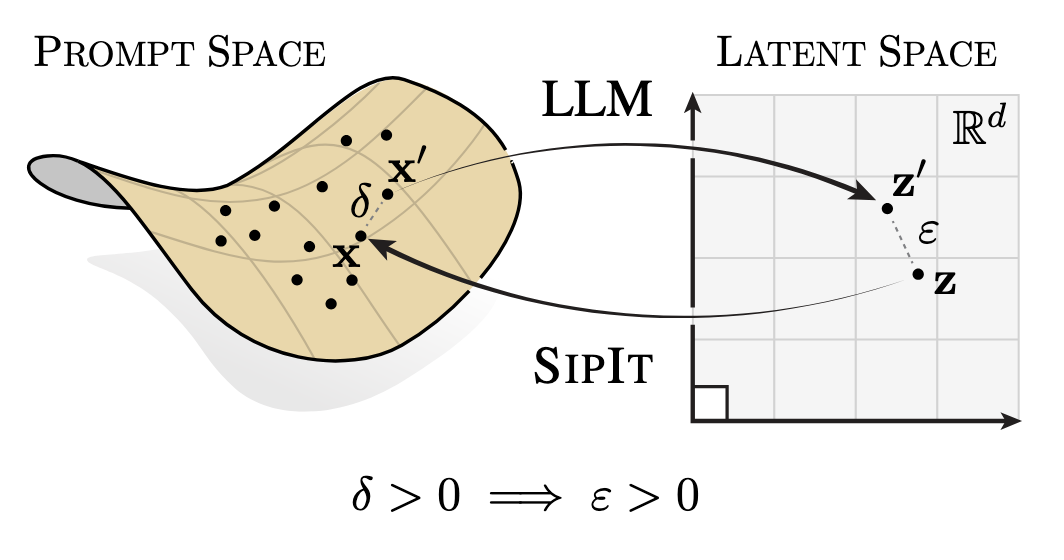

I think one of the main contribution of the paper is to slightly

change the context: they see language models as functions from a

prompt (i.e. a finite sequence of discrete tokens) to activations

on the output layers (vectors). The

function we are studying: from prompt space (sequence of tokens) to

latent space (vector of activations).

The

function we are studying: from prompt space (sequence of tokens) to

latent space (vector of activations).

Formally, we have a finite vocabulary \(\mathcal{V}\), and context length \(K\). From a sequence of tokens \(s \in \mathcal{V}^{\leq K}\) and parameters \(\mathbf{\theta}\), the language model gives us last-token representations \(\mathbf{r}(s, \mathbf{\theta}) \in \mathbb{R}^d\).

The central claim of the paper is that this function is injective.

Why is injectivity important?

Since the various components of the language models are not themselves injective, people tend to assume that there is some “forgetting” and privacy is built into all language models. Since the input prompt is transformed into an intermediate representation that goes through many transformations, information is lost and the input prompt cannot be reconstructed exactly. This intuition is wrong.

This has practical consequences for systems that store intermediate activations (e.g. embeddings), in the assumption that this is somehow more secure, or more respectful of their users privacy, than storing the user inputs directly. In practice, all the information is in the activations, and the paper provides both a formal proof and a practical reconstruction method.

Structure of the paper

The paper has two main parts.

- The theoretical part defines a Transformer-based language model mathematically as a function from sequences of tokens to real-valued vectors. In this context, they prove that language models based on common blocks (feed-forward layers, embedding layers, self-attention blocks, common activations, etc) are almost surely injective after random initialization of the parameters, and that this property is preserved during training.

- The practical part builds on these insights and builds a fairly straightforward algorithm to reconstruct user inputs from the activations of any intermediate layer, including the output layer. They show 100% reconstruction accuracy on widely-used language models.

The theoretical argument

A primer on analytic functions

To prove the main results, the paper uses the notion of

analyticitySee Appendix A of the paper for the full

background on analytic functions.

. Analytic functions are highly

regular, actually even “smoother” than infinitely differentiable

functions. It is this “smoothness” that will have important

consequences for proving injectivity.

Intuitively, analytic functions are “locally polynomial”:

Let \(\mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m\) be open. A function \(f : \mathcal{U} \to \mathbb{R}\) is real-analytic on \(\mathcal{U}\) if, for every \(\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{U}\), there exists coefficients \(\{c_\mathbf{\alpha} \in \mathbb{R}\}_{\alpha \in \mathbb{N}^m}\) and \(r>0\) such that

\[ f(\mathbf{x}) = \sum_{\mathbf{\alpha} \in \mathbb{N}^m} c_\mathbf{\alpha} (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y})^\mathbf{\alpha} \]

for all \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{U}\) with \(\lVert \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y} \rVert_2 < r\).

The set of analytic functions on \(\mathcal{U}\) is denoted by \(C^\omega(\mathcal{U})\).

Intuitively, not only the function is infinitely differentiable, and therefore can be locally approximated by its Taylor series, but actually the coefficients are zero after some point, so the function is locally a polynomial. This gives enormous regularity guarantees, and analytic functions are among the most well-behaved.

A vector-valued function is analytic if all its components are analytic, and we can similarly extend the definition to matrix-valued functions. This is very important for our discussions since the component blocks of Transformers are often matrix-valued, e.g. attention layers.

Importantly, the set of analytic functions is closed under common operations: addition, product, quotient, and composition. This means that we only have to prove the analyticity of common building blocks of Transformers, and through addition and composition the analyticity of the overall function will be immediately proven.

Moreover, analytic functions have a key property relating to their zero sets:

Let \(\mathcal{U} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m\) be connected and open, and let \(f \in C^\omega(\mathcal{U}; \mathbb{R}^n)\). If \(f \not\equiv \mathbf{0}_n\), then its zero set \[ Z(f) := f^{-1}(\{\mathbf{0}_n\}) = \{\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{U} : f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{0}_n\} \] has Lebesgue measure zero in \(\mathbb{R}^m\).

The proof can be found in Mityagin (2020)The paper actually cites the (identical) preprint version.

.

The gist is simply this: if \(f\) is not zero everywhere, then it is zero almost nowhere. If there is an entire continuous region where \(f\) is zero, it means that \(f\) is zero everywhere! This is a very strong property of analytic functions: fundamentally, they are so regular that if they are zero on any significant portion of their domain, their smoothness imposes that they become zero everywhere.

This proposition is key to the paper as it will be used to prove injectivity. We can now go on to the actual results of the paper.

Language models are analytic

A language model is a composition of many building blocks. Transformer blocks are themselves composed of self-attention layers and MLPs, which are themselves compositions of stacking operations, normalizations, softmax, exponentials, and polynomials. By going bottom-up, we can start from basic blocks (polynomial functions, the exponential function), show that they are analytic, and since analytic functions are closed under composition, show that the entire language model is analytic.

The proofs that these building blocks are analytics are detailed in Appendix A of the paper. The full language model is defined mathematically as a composition of these building blocks in Appendix B, with Proposition B.3 putting everything together and proving that Transformers are analytic.

Injectivity at initialization

Let us draw a set of parameters \(\mathbf{\theta}\) at random, from a distribution with a density. For any two prompts \(s, s' \in \mathcal{V}^{\leq K}\), the probability that the output activations \(\mathbf{r}(s, \mathbf{\theta})\) and \(\mathbf{r}(s', \mathbf{\theta})\) are equal is zero.

This is because the function \(\mathbf{\theta} \mapsto \mathbf{r}(s, \mathbf{\theta}) - \mathbf{r}(s', \mathbf{\theta})\) is a sum of analytic functions, and is therefore analytic. By the key proposition above, its zero set has measure zero. So by drawing random parameters \(\mathbf{\theta}\), you have almost surely \(\mathbf{r}(s, \mathbf{\theta}) \neq \mathbf{r}(s', \mathbf{\theta})\).

We have just proven that if \(s \neq s'\), then, with probability 1 over \(\mathbf{\theta}\), we have that \(\mathbf{r}(s, \mathbf{\theta}) \neq \mathbf{r}(s', \mathbf{\theta})\) i.e., \(\mathbf{r}\) is injective!

Injectivity is preserved during training

However, we only draw \(\mathbf{\theta}\) at random during initialization. What if during training, as \(\mathbf{\theta}\) changes, the language model loses its injectivity?

It turns out that gradient descent itself is also analytic (and so are

its variants, stochastic gradient descent, minibatch GD, etc). It is

therefore once again very smooth, and can only stretch and bend the

parameter space, but not collapse regions of positive volume into

single points. So as the parameters change during training, the points

that are apart stay apart and do not collapse onto each

otherThe argument is made formally in the paper using

topological properties of the Jacobian of the gradient descent

function. I won’t go into the details here, see Section 2 of the paper

for an overview, and Appendix C for the full proof.

.

The injectivity property established at initialization is therefore preserved at each step of the training. This concludes the main result of the paper: a fully-trained language model based on Transformers is injective. Two different input prompts will always lead to two different output activations in the final layer (and in any intermediate layer for that matter).

Remarks

The paper bases all the proofs on a definition of a “standard” language model based on Transformers. However, there are architecture choices that can break the fundamental hypotheses. In particular, some activation functions like ReLU are not analytic (indeed, it is not even differentiable), and things like quantization also break the analytic property of the entire model. In these cases, the model will not be injective.

However, all modern language model architectures use smooth

activationsSee this great article on SwiGLU and family for an

overview of activation functions used in LLMs.

, and quantization is not the norm

everywhere. As we will see in the next section, the theoretical result

hold very well in practice for LLMs that are widely used today.

Practical application

Proving a theorem might not be enough, as there are plenty of things that are ignored in the mathematical formulation (e.g. floating-point precision). Moreover, real-world LLMs are very complex systems with thousands of building blocks. For instance, activation functions are part of a very active research domain and change frequently, so there is no guarantee that all activation functions found in the wild follow the requirements of the theorem.

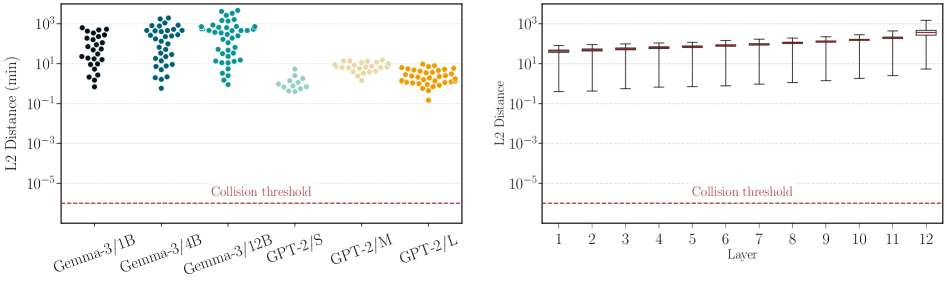

The first practical test is to check for collisions: two input prompts that lead to the same activation vector. If we can exhibit two sequences of tokens like this, we will have broken the injectivity.

For large vocabularies, the input space is too big to be checked exhaustively, so they can’t check everything. Instead they start with a dataset of real-world prompts and find the ones that are the closest in the output. They append all the possible sequences of tokens to these prompts. Therefore the test is “exhaustive” starting from “prefix” prompts that were already very close.

What they find is that all input pairs are very far from a collision threshold of \(10^{-6}\) (probably chosen to account for floating-point error). As this check is not truly exhaustive and the thresholds have been fixed somewhat arbitrarily, it’s not very significant, but it acts as a nice “sanity check” for the theory.

Distance between final layer and intermediate layer outputs

for the “exhaustive” check on input prompts. All are significantly

above the collision threshold as defined in the paper.

Distance between final layer and intermediate layer outputs

for the “exhaustive” check on input prompts. All are significantly

above the collision threshold as defined in the paper.

The second practical experiments is to exploit the injectivity result to build an algorithm to invert a language model. Starting from the last-layer activations, they build a simple gradient-guided search that reconstruct the input sequence of tokens. The results are impressive: they get 100% token-level accuracy on all prompts, and in a remarkably quick process. The following results are for the GPT-2 Small model:

| Method | Mean Time (s) | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| HardPrompts | 6132.59 ± 104.61 | 0.00 |

| BruteForce | 3889.61 ± 691.17 | 1.00 |

| SipIt | 28.01 ± 35.87 | 1.00 |

Conclusion: rebuilding our intuition

Expressivity and regularization

Transformers (and neural networks in general) are very useful because they generalize very well. The class of learned functions needs to be very large to be as expressive as possible, but still constrained to avoid overfitting. The regularization built into our language models can be understood as properties of the functions they represent. Analytic functions are a class of very smooth, very regular functions, that have a lot of nice property, so it is no accident that they are very good targets of a machine learning algorithm.

Curse of dimensionality

The main result of the paper does not seem so unintuitive if its hypotheses are laid out clearly. What we have is a function with inputs on a discrete space (finite sequences on a finite vocabulary), and outputs in continuous, high-dimension vector space. Since the output space is so much larger, it would actually be very surprising that a non-pathological function makes several inputs “collapse” into a single high-dimension vector!

Moreover, there is an instance of the curse of dimensionality: if you draw two vectors with random directions in a high-dimension space, they will very probably be orthogonal (Vershynin 2018, sec. 3.3.3). High dimensions tend to “push everything to the edges” and so collisions become increasingly unlikely. So another way to see this result is that it is unintuitive only because probability on high-dimension vector spaces is in itself quite unintuitive!