The Bulgarian Solitaire

Imagine you are the director of a unit in a large company. You have 5 teams, with various numbers of people in each team. An important new project has come up, and you would like to set up a new team to tackle it. The problem is: you don’t have any budget to hire new people!

What can you do? Well, you could take one person from each existing team, and build a new team with these 5 people.

It works well for a while, but of course soon enough, a new project comes up, and you still don’t have any additional budget! It worked the first time, so you reshuffle the teams once more in the same way. One of the existing team had only one person left, so they go to the newly created team and their existing team just disappears.

Now the CEO is getting concerned with your unconventional management practices. She summons you to her office and asks you: What would happen if you do this repeatedly for every new project? How many teams will you end up with, with how many people in each one of them?

The Bulgarian Solitaire

Instead of this (admittedly far-fetched) management scenario, you can

do the same process with playing cards. You have \(n\) cards divided

arbitrarily into several piles. At each step, you remove one card from

each pile and collect them in a new pile next to the existing ones. If

you repeat this operation, how many piles of cards will you get? With

how many cards in each of them? This problem is called the Bulgarian

Solitaire. It is described in this paperWhich also describes the

history of the problem, including why it is called “Bulgarian”.

.

With \(n\) cards, the Bulgarian Solitaire is an example of a discrete dynamical system on partitions of \(n\). A partition is an unordered sequence of numbers that sum to \(n\). For instance, \((4,3,2,1)\) and \((8,3,2,2)\) are partitions of 15. At each step, the Bulgarian Solitaire will transform a partition like \((8,3,2,2)\) into a new one, in this case \((7,2,1,1,4)\) (the new pile is at the end, but we don’t care about the order so we can also write it as \((7,4,2,1,1)\)).

What we are trying to understand is in fact a standard question in dynamical systems: where is the system going? Are there stable states, cycles? What are they?

Visualizing the Bulgarian Solitaire process

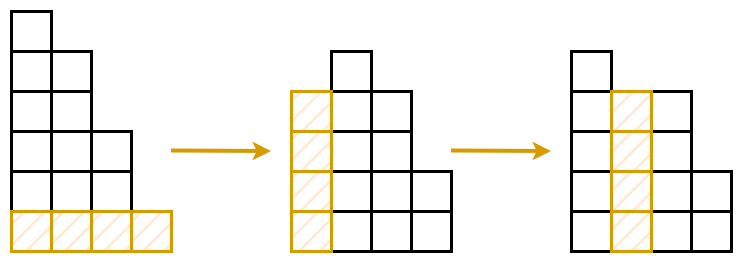

As a first example, let’s take \(n=10\) cards, in piles of 4, 3, and 3 cards. We take one card from the top of each pile (in orange), and we make a new pile of size 3:

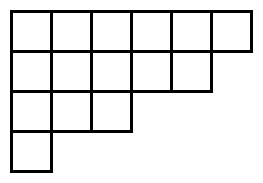

Visualizing cards like this is not very practical, but as it turns out, mathematicians have already devised a nice way to visualize partitions: Young diagrams. They represent a partition as rows of boxes. For example, the partition \((6,5,3,1)\) of the number 15 can be visualized as:

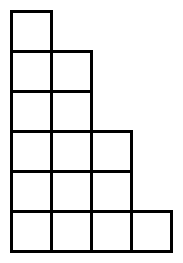

In our cases, we can rotate the Young diagram by 90° so that it looks more like piles of cards:

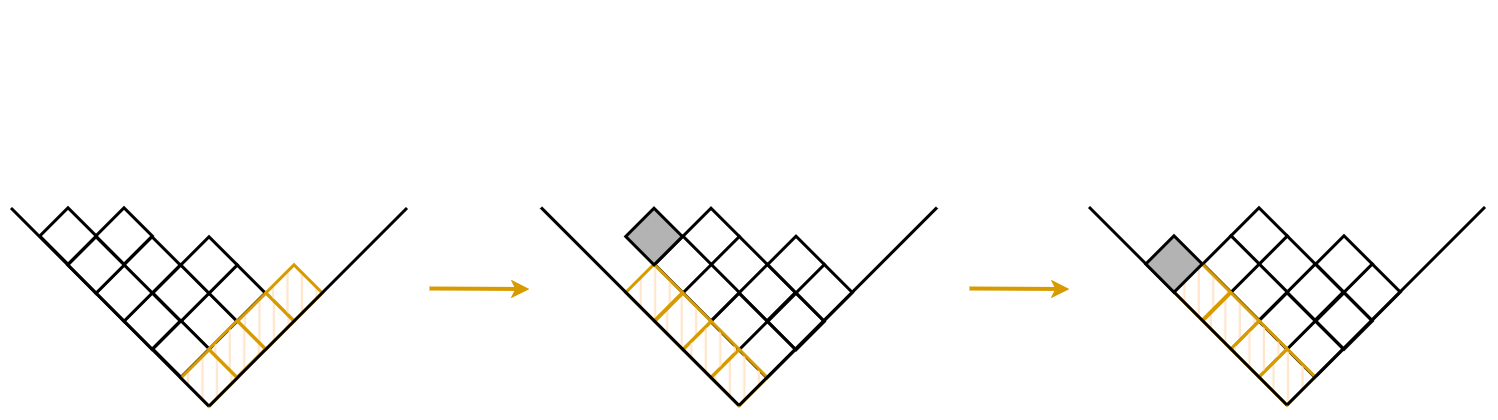

A step in the Bulgarian Solitaire will look like this:

We take one card from each pile (highlighted in orange in the diagram above), and create a new pile from them. Then we reorder the piles so that they are sorted by decreasing size.

Convergence of the Bulgarian Solitaire

Now, if you try the Bulgarian Solitaire with 15 cards, for every possible starting position, you will end up with 4 piles of size 1, 2, 3, and 4. It turns out that this pattern can be observed consistently:

When the number of cards \(n = k(k+1)/2\) is triangularTriangular numbers are the sums of consecutive

integers: 1, 1+2, 1+2+3, etc. They get their names from the fact that

they can be arranged in a triangle. (OEIS: A000217) (Image from

Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA.)

,

the Bulgarian Solitaire will converge to piles of size 1, 2, …, \(k\).

How can we prove this?

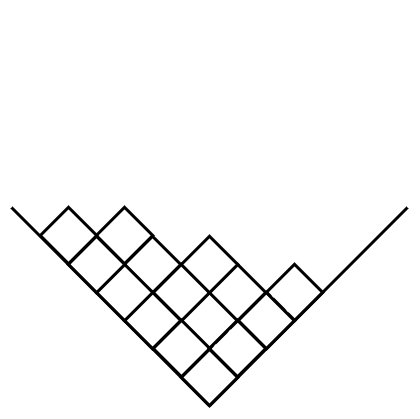

There is a nice trick: we rotate (again!) our Young diagram by 45°:

When we do a step in the Bulgarian Solitaire, we move around the boxes:

Sometimes we can see that a box (in grey here) is above an empty space, and therefore it falls down. This corresponds to cases when there is a need to reorder the piles so that they remain in order of decreasing size.

We can see that at each step, the total potential energy of the boxes either stays the same (when all boxes are still resting on other boxes or on the edges) or decreases (when a box is above an empty space and falls down). And the lowest possible potential energy is reached when the configuration is fully triangular, when boxes are spread evenly across all piles!

So now we just need to prove that all configurations will end up at this minimum of potential energy, i.e. that there is no local minimum that prevents the system from reaching this global minimum.

Imagine we are not at this triangular position. Since the total number of boxes is triangular, there is necessarily one layer with an empty space for a box, and one layer above with an additional box. At each step, the boxes will “rotate”, and the empty space and the additional box will move one space to the right. If the layer with the empty space is of size \(k\), the layer above it will be of size \(k+1\), and these numbers are relatively prime. After a certain number of steps, the additional box will be directly above the empty space and will fall down.

So no configuration that is not fully triangular is stable: after a certain number of steps, the potential energy will decrease. The detailed proof can be found in section 2 of the paper.

Simulating the Bulgarian Solitaire

Let’s simulate the process (in Python) to visualize the convergence. The script will generate all partitions of a given integer \(n\), and generate the transition graph of the Bulgarian Solitaire. If a step of the Bulgarian Solitaire transforms partition \(p_1\) into partition \(p_2\), we will draw an edge between \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

We’ll start by defining helpful type aliases: a partition is a tuple of ints, and the graph we will generate is a dictionary from partitions to partitions.

type Partition = tuple[int, ...]

type Graph = dict[Partition, Partition]Next, we need a function that enumerates all possible partitions of a given integer \(n\). It is built recursively: for all possible prefixes \(0 < k \leq n\), the partitions we are looking for consist of \(k\) followed by all partitions of \(n-k\).

from collections.abc import Generator

def integer_partition(n: int) -> Generator[Partition]:

if n <= 0:

return

def find_partitions_recursive(target: int, current_partition: list[int]):

if target == 0:

yield current_partition

return

max_val = current_partition[-1] if current_partition else target

for i in range(min(target, max_val), 0, -1):

current_partition.append(i)

yield from find_partitions_recursive(target - i, current_partition)

# Backtrack

current_partition.pop()

yield from map(tuple, find_partitions_recursive(n, []))The step function is the Bulgarian Solitaire itself:

def step(partition: Partition) -> Partition:

next = [len(partition)] + [k - 1 for k in partition if k > 1]

return tuple(sorted(next, reverse=True))We can now compute the transition graph:

def compute_graph(n: int) -> Graph:

return {partition: step(partition) for partition in integer_partition(n)}Now for display, we generate some Graphviz code. The colors are adapted for viewing directly in the terminal.

def print_graphviz(graph: Graph) -> None:

print("""digraph {

bgcolor="transparent";

node [shape="rect", fontcolor="white", color="white"];

edge [fontcolor="white", color="white"];

""")

for k, v in graph.items():

print(f' "{k}" -> "{v}";')

print("}")To finish, let’s add a command-line interface:

import argparse

def main():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("n", type=int)

args = parser.parse_args()

graph = compute_graph(args.n)

print_graphviz(graph)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()The script can then be called directly:

# Save the graphviz file

python bulgarian_solitaire.py 10 > graph10.dot

# Generate a PNG graph

python bulgarian_solitaire.py 10 | dot -Tpng > graph_10.png

# Display the image directly in the terminal (if it supports image display)

python bulgarian_solitaire.py 12 | dot -Tpng | viu -Here is the output for \(n=6\):

And for \(n=10\):

As we can see, all partitions indeed converge to the triangular configurations \((3,2,1)\) and \((4,3,2,1)\).

Now what happens when the number \(n\) is not triangular?

For \(n=7\):

The dynamical system converges to a cycle between \((4,2,1)\), \((3,3,1)\), \((3,2,2)\), and \((3,2,1,1)\). When we look at this cycle, we realize that it is the triangular configuration \((3,2,1)\), plus an additional box cycling above.

For \(n=8\):

Here we get two connected components in the graph. And here again, we get the triangular partition but with two additional boxes cycling above.

This property can be proved (Theorem 2 in the paper), and the number of connected components can be computed exactly for all \(n\).

Conclusion

The Bulgarian Solitaire is a nice example of a discrete dynamical system. The proof is particularly interesting because it relies on visualization and physical intuition about the “potential energy” of the system, which translates directly into the formal proof.

The paper also mentions generalizations. I am interested in particular in the stochastic Bulgarian Solitaire. Instead of taking one card from each pile at each step, we take one card from each pile independently with probability \(0<p<1\). The dynamical system becomes a Markov chain, and it would be interesting to study (even experimentally) its convergence properties.

Bonus: BQN implementation of the simulator

First, the Step function computes one step of the Bulgarian

Solitaire. It removes 1 from each pile (¯1⊸+), removes the piles

that became empty (0⊸≠), adds a pile of the original size (≠∾), and

sorts the piles for consistency (∨).

Step←∨≠∾(0⊸≠⊸/¯1⊸+)The Partitions function generates all partitions of a given

integer. Conveniently, this was already available in BQNcrate!

Partitions←{∾⊢´∾⟜(<-⟜↕∘≠{𝕨∾¨∾(-𝕨⌊≠𝕩)↑𝕩}¨⊢)⍟𝕩⋈⋈⋈↕0}We can now compute the graph, by first computing all partitions of the

input, then building the edges by calling Step on each partition.

ComputeGraph←{>(⊢⋈Step)¨Partitions𝕩}We now generate and print the graphviz code:

EdgeToGraphviz←{∾⟜(""";"∾@+10)5↓∾""" -> """⊸∾¨•Fmt¨𝕩}

graphvizheader←"bgcolor=""transparent"";

node [shape=""rect"",fontcolor=""white"",color=""white""];

edge [fontcolor=""white"",color=""white""];"

ToGraphviz←{"digraph {"∾graphvizheader∾(∾EdgeToGraphviz¨<˘𝕩)∾"}"}

n←•ParseFloat⊑•args

•Out ToGraphviz ComputeGraph nSimilarly to the Python version, we can run the script with:

bqn bulgarian_solitaire.bqn 6 | dot -Tpng > graph_6.png